The Janitor Who Taught the Surgeons

By Matt Stone

At The Grounded, we honor truth that survives without applause.

This is the story of a man who saved thousands of lives while the system labeled him a janitor.

It’s November 29, 1944, and the room smells like bleach, metal, and God.

A single infant lies on the table, her lips the color of twilight, her body a dark shade of blue.

Her tiny chest rises like a dying bird.

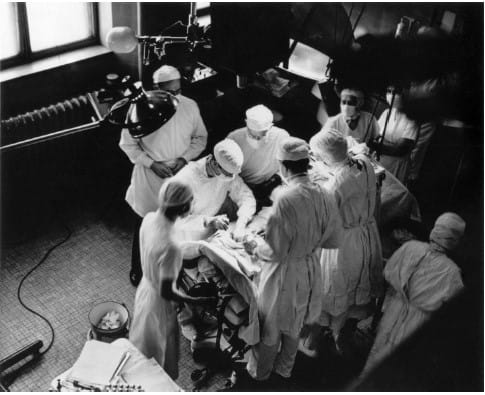

Dr. Alfred Blalock stands at the head of the table, scalpel trembling over the blue-veined throat of a child who may not live another hour.

Beside him stands a man in a white coat that doesn’t fit the hierarchy of the room.

He’s not on the payroll as a doctor, not even a technician.

He’s listed as a janitor. The man observing him is technically a "custodian." Delegated to cleaning toilets and mopping floors. But he is not just any janitor.

Every surgeon in the room knows who the real master is.

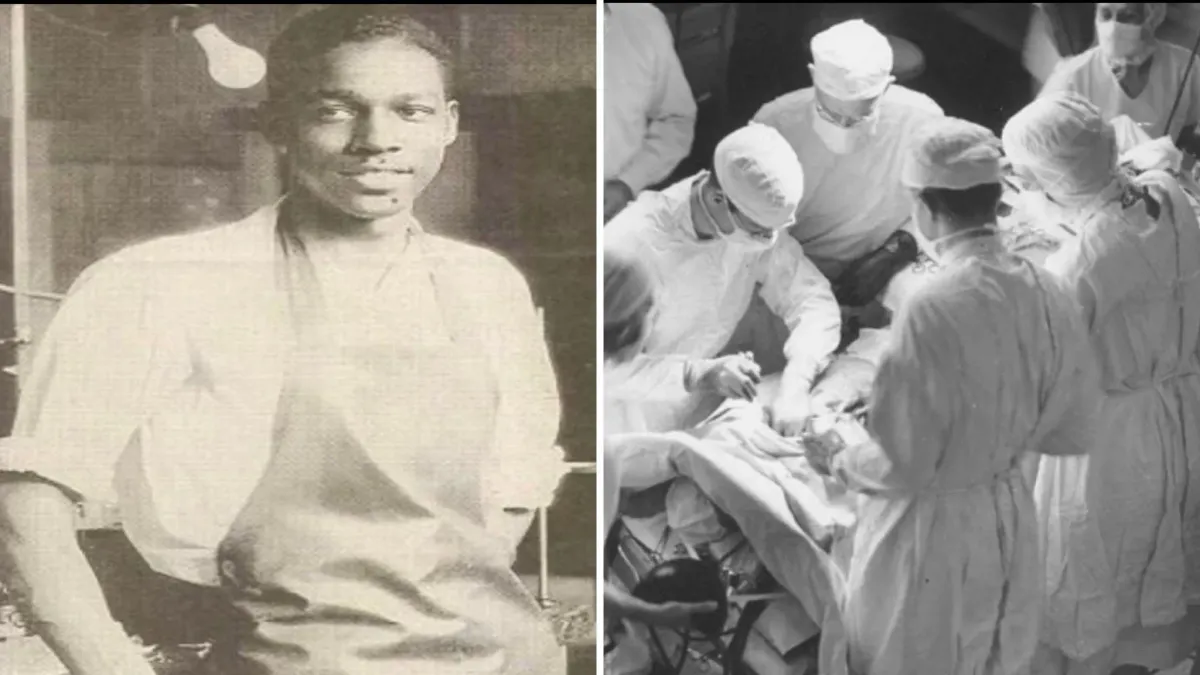

Vivien Thomas.

A Black man with steady hands, calloused by work the world refused to name as genius. He stands on a wooden stool, because the table was built for taller men, whiter men, credentialed men—and he guides Blalock’s hands through the incision and entire process.

“Clamp there. Now stitch along the artery.”

His voice is calm. Controlled. Almost prayerful.

The baby lives.

And history almost forgets the man who made it happen.

I first read about Vivien Thomas when I was supposed to be doing something else—editing papers, writing an essay, filling out some form that probably didn’t matter. I was tired, burnt out, caught in that American loop of proving worth to systems that don’t know how to see it.

But this name, Vivien Thomas, stopped me cold.

A man paid as a janitor who invented heart surgery.

Not metaphorically. Literally.

I thought of all the times I’ve met people whose brilliance couldn’t fit inside their job title.

The army medic quoting Nietzsche, the counselor keeping people breathing, the janitor humming gospel, the ones whose hands hold the country together.

America’s full of them, hands dirty, eyes steady, carrying a kind of wisdom that never makes it into a résumé.

Vivien Thomas was one of them.

He was born in 1910 in Lake Providence, Louisiana—named after a hope no one around him could afford. He grew up in Nashville, finished high school, and had plans for medical school. But then came 1929, the Great Depression, and every door he’d dreamed of opened only to close again.

When he finally found work at Vanderbilt, it wasn’t in a lab coat but on a janitor’s wage. His boss, Dr. Alfred Blalock, ran a surgical research lab studying shock. The work was dirty, bloody, precise. Vivien started cleaning glassware, sweeping floors. Then one day Blalock noticed something unusual: Vivien didn’t just clean the instruments. He studied them. Memorized them. Reorganized them to fit the rhythm of a surgery.

Soon Blalock was handing him scalpels instead of brooms.

And Thomas, without a college degree, without a single medical credential, began designing experiments, inventing surgical tools, and developing procedures that would eventually define modern cardiovascular surgery.

But Vanderbilt’s paybook still said “janitor.” The father of heart surgery was a janitor because of the color of his fucking skin.

I think about that title sometimes—what it meant in 1930s Tennessee for a Black man to walk into a white medical lab, outthink everyone in the room, and still be called a janitor.

Maybe that’s why I feel him so deeply. Because I know what it’s like to be invisible while doing something extraordinary.

To be told, you don’t belong here, while quietly saving the day anyway.

Vivien Thomas lived that contradiction every single day of his career.

He learned by doing, by cutting, by watching life slip and return under his hands. He was self-taught in the language of arteries and veins, the choreography of life itself. He trained surgeons who didn’t know how to train him. He trained surgeons who went on to be the Chiefs of Surgery in hospitals all over the country.

When Blalock left Vanderbilt for Johns Hopkins in 1941, he took Thomas with him. But Hopkins wouldn’t even put his name on the research roster. They classified him as a janitor once again, a man with no degree, no title, just skill so rare the surgeons whispered about it like myth.

And still he showed up. Coat pressed. Tools clean. Precision in every movement.

Then came the Blue Baby Problem—infants born with hearts too malformed to carry oxygen, turning their skin ghost-blue. No one had ever successfully operated on a human heart before. Surgeons considered it sacred territory: untouchable, forbidden.

But Vivien Thomas had already done it—on hundreds of dogs. He’d built the instruments himself, tested every angle, refined the procedure until it was as natural as breathing.

When the day came for the first human operation, Blalock took the lead.

But it was Thomas who guided him.

Standing on that stool, Thomas leaned over the shoulder of the man history would call a pioneer and whispered,

“Clamp there. Yes, now tie it off.”

It was Vivien’s choreography—the Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt—that gave that little girl her color back. Her lips went from blue to pink. Her lungs filled. Her parents wept. For his trouble, the shunt was initially called the Blalock-Taussig shunt, once again erasing his name from history.

And yet the medical journals insisted on listing only Blalock and Taussig.

Thomas’s name didn’t appear.

The man who built the road wasn’t allowed to walk on it.

The story gets under my skin because I can feel the tension in it.

The need for recognition versus the quiet pride of knowing the truth.

I’ve lived that tug-of-war too, between proving myself and keeping my soul intact.

Sometimes greatness doesn’t roar. It just keeps showing up.

And that’s what Vivien did.

He trained generations of surgeons, most of them white, many of them now legends in their own right. They called him Professor Thomas long before Hopkins did.

But outside those walls, America was still Jim Crow. He couldn’t sit in the same restaurants as the men he trained. Couldn’t buy a home in their neighborhoods. Couldn’t walk through the front door of the hospital that depended on his genius.

There’s a kind of holiness in restraint—when you know what you’re capable of and still choose to act from dignity instead of rage.

That’s what separates men like Vivien Thomas.

I imagine him walking home after a day in the operating room. Coat folded over one arm, gloves in his pocket.

Maybe the Baltimore air stung his skin that night, the way injustice stings but never breaks you.

Maybe he smiled to himself, thinking of the babies who would breathe because of his hands.

He didn’t need applause.

He just needed the work to matter.

And it did.

Decades later, Johns Hopkins finally gave him an honorary doctorate.

He was 66 years old.

By then, the men he trained were department heads around the world. The procedures he invented were standard practice. He made legends out of countless surgeons.

At the ceremony, they called him “Doctor Thomas.”

But the truth is, he’d earned that title long before anyone dared to say it out loud.

There’s a line from the Washingtonian article that became the HBO movie about his life: Like Something the Lord Made.

That’s what his work was.

Not mechanical. Not theoretical. Divine.

He didn’t just fix hearts; he redefined what it meant to have one.

When I write about him, I think of every person I’ve met who’s been written out of their own story.

The single mother cleaning hotel rooms who writes poetry on her lunch break.

The ex-convict teaching kids to build gardens in abandoned lots.

The addicts I’ve sat beside in group therapy who’ve seen more of life’s truth than half the philosophers I’ve read.

Vivien Thomas is their patron saint.

A man whose faith wasn’t in religion, but in repetition.

In showing up. In believing that hands can carry purpose even when titles don’t.

There’s something tragic about how often America needs permission to recognize greatness when it’s wearing dark skin or working-class clothes.

We demand degrees, not depth.

Credentials, not conscience.

We’ve built entire systems to measure potential by proximity to privilege.

Vivien’s story is the antidote to all that.

It reminds us that skill doesn’t need permission.

That genius doesn’t wait for validation.

That the world runs on the quiet excellence of people it refuses to name.

If I could speak to him now, I’d tell him what his story did for me.

I’d tell him that every time I feel small, every time I’m back at the bottom of some new mountain, I think of him standing on that stool, taller than any man in the room.

I think of how calm he stayed. How he never stopped teaching, even when the world refused to call him a teacher.

And I’d tell him I get it—the loneliness of doing great work in silence. The ache of wanting to be seen not for glory, but for truth.

We both learned that legacy isn’t about fame. It’s about faith—faith that your work will outlive the blindness of your time.

When Vivien Thomas finally retired, he left behind a generation of surgeons who spoke his name like scripture. They remembered his hands guiding theirs, his voice quiet but certain.

He died in 1985, but in a way he never really left. Every newborn who takes a first clean breath because of that shunt carries his fingerprint. Every surgeon who trains under another who trained under him keeps a fragment of his rhythm alive.

The janitor became the foundation.

The shadow became the source of light.

Sometimes I wonder if he knew how much he changed the world.

If he ever looked at his reflection and saw what history couldn’t.

If he felt the weight of what he’d built, or if humility was his armor.

Maybe he just wanted to keep working.

Maybe the act itself was enough.

And maybe that’s the lesson.

The world will misname you. It will underpay you, overlook you, and pretend not to notice when you make it better.

But if you keep showing up, if you keep doing the work anyway, eventually your story will crawl out of the shadows.

Vivien Thomas taught the surgeons.

He taught the world.

And he taught people like me that purpose isn’t about being recognized. It’s about being ready.

When your moment comes—when the world finally looks up from its hierarchy and asks, “Who can save this life?”

You want to be the one standing there, steady hands, quiet heart, ready to say,

“Clamp there. Now tie it off.”

Vivien Thomas proved that truth doesn’t need a title.

That’s why The Grounded exists, to make sure stories like his never stay buried again.

Comments ()